hiccups are a reflex of the diaphragm

and other randomly selected undergrad lessons & learnings

Throughout my cogs BSc at UBC, I had a little note page (sometimes a specific highlight colour) where I collected certain bits of information that, for me, went way beyond the classroom. This included ideas which triggered great personal realizations, conspiracy-board-esque ‘aha’ moments, or tidbits I came to think about regularly. This is a *start* at collating and sharing some of those lovely bits.

I thought to write on this for my own self-indulgent reflection, but I hope any aspiring cogs students or curious readers might find something in here that sticks. All of these together make for a hefty post, so my tip is to return to it chunk by chunk, like a little collection of short stories!

An optional-to-read meta aside on context, purpose, and approach: On the plight of getting dizzy after a carnival ride

Graduating has finally landed me in a place where I have a lot more time to pursue all of those interests and ideas that were too big or too precious to jam into my coursework and extracurriculars. Many of those things I’ve been revisiting first appeared in the type of notes-to-self I wanted to share here.

One of my few relative ‘constants’ during this transitional period has been my continuing research at Beck’s lab, though it too has adapted to this new era. The work I do now largely involves the revisiting of many of those morsels I had saved for later. But, both in my personal life and lab work, I’ve found myself a little surprised and often completely frozen by how tall that stack became. Nested among the stacks of large goals were even taller stacks of the littlest ideas, references, and inspirations. It’s become a perfect display of both the strengths and challenges of the ‘creative neurodivergent/ADHD brain’.

We set this post up as a practice in breaking the ice of overwhelm by just doing something, just putting thoughts out with few stakes or expectations of comprehensiveness. Before I knew it, I took the goal of a simple blog post on a topic of my choosing and almost turned it into the major undertaking of reviewing, filtering, and consolidating the entirety of my notes from the past five years…

Consider this self-soothing and self-humanizing aside of mine Lesson & Learning #0: learning and unlearning ways of achieving goals in the context of self-defined work.

With that, here is my doodle. Just a doodle! And a snapshot! Of some of those oh-so-sprawling sticky notes and highlights. I’ll include some context, but do not hold me liable for an accurate academic retelling of any of these topics! This is about what these topics have come to mean to me. The morsels that have made it to this article were randomly selected, though I have ordered them chronologically. Now off we go!

Lesson & Learning #1: intrinsic vs extrinsic motivations and internal vs external locus of causality

[From PSYC102, Intro to developmental, social, personality, and clinical psyc]

This was one of the earliest things in my degree that stuck. Just shortly before we all got sent home due to covid, I listened to one of Darko Odic’s optional bonus recordings he shared with the class. In it, he explained the myth of ‘do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life’. There’s always a risk when turning hobbies into a paid job as it can cause a shift from intrinsic motivation to extrinsic motivation. For some first-year psyc background: intrinsic motivation is marked by a sense of reward/value felt and generated by oneself (e.g. personal enjoyment, sense of mastery), while extrinsic motivation is marked by an externally generated reward (e.g. getting paid). While intrinsically motivated activities tend to be engaged with at more variable intervals whenever one seeks them out, extrinsically motivated activities might be completed more readily when the reward is highly valued and salient enough, however, motivation can steeply drop as we devalue the reward or it becomes more distal. So, to circle back to the context of a hobby-turned-job, taking activities that we intrinsically enjoy and suddenly getting externally rewarded for them can cause the feeling of intrinsic reward to fall to the side, making it mainly extrinsically rewarded. Feeling the intrinsic motivation dissipate can be demoralizing and disorienting. Now that your hobby has become work it might feel as though you no longer have hobbies you enjoy for fun, leaving this gap in your identity.

As with much of psychology (and in general academic writings I’m drawn to) I find this to be a very fancy and articulate way of putting long-time intuitions of mine. However, having a structured and ‘justified’ way to think about it became useful when facing lofty questions on how to stably incorporate my interests into my career goals (which I face often).

Ah, but didn’t I also have ‘internal vs external locus of causality’ in the heading for this one? I used to mix these two pairs up so often that every time I think of one I think of the other, so I figured I might as well pay homage to that experience and group them here.

As with intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivations, internal vs. external locus of causality was a classic piece of first-year psychology that has stuck with me for its usefulness as a tool in self-reflection and growth. It sparked a lot of thought regarding the importance of finding nuance in one’s sense of control. In psyc102 we were taught that people with more of an internal locus of causality (which I relate to feeling ‘in control’) tend to be more organized, friendly, healthy, and social, while an external locus of control (feeling things are out of your control) is associated with more anxiety/neuroticism. However, I also felt there had to be a balance with the recognition and acceptance of things out of one’s control. In fact, when I was following along to that slide in class, I thought the associations would be the other way around since my mind jumped to thinking of an ‘everything is my fault’ type mentality. Of course, as my education progressed, I found so many more nuanced, supported, and intuition-aligned ways of describing these things. Yet still, it was the start of a thread in developing my understanding of locus and sense of control as key variables in how we worldbuild and understand ourselves in the world.

Lesson & Learning #2: modelling the effect of opportunity cost and systemic disadvantage on fairness norms

[From COGS303 Methods in Cognitive Systems]

Now, disclaimer, this one is HEFTY. It requires quite a lot of context but I thought it was cool. So if you happen to be into computer models of human behaviour, you’re in luck.

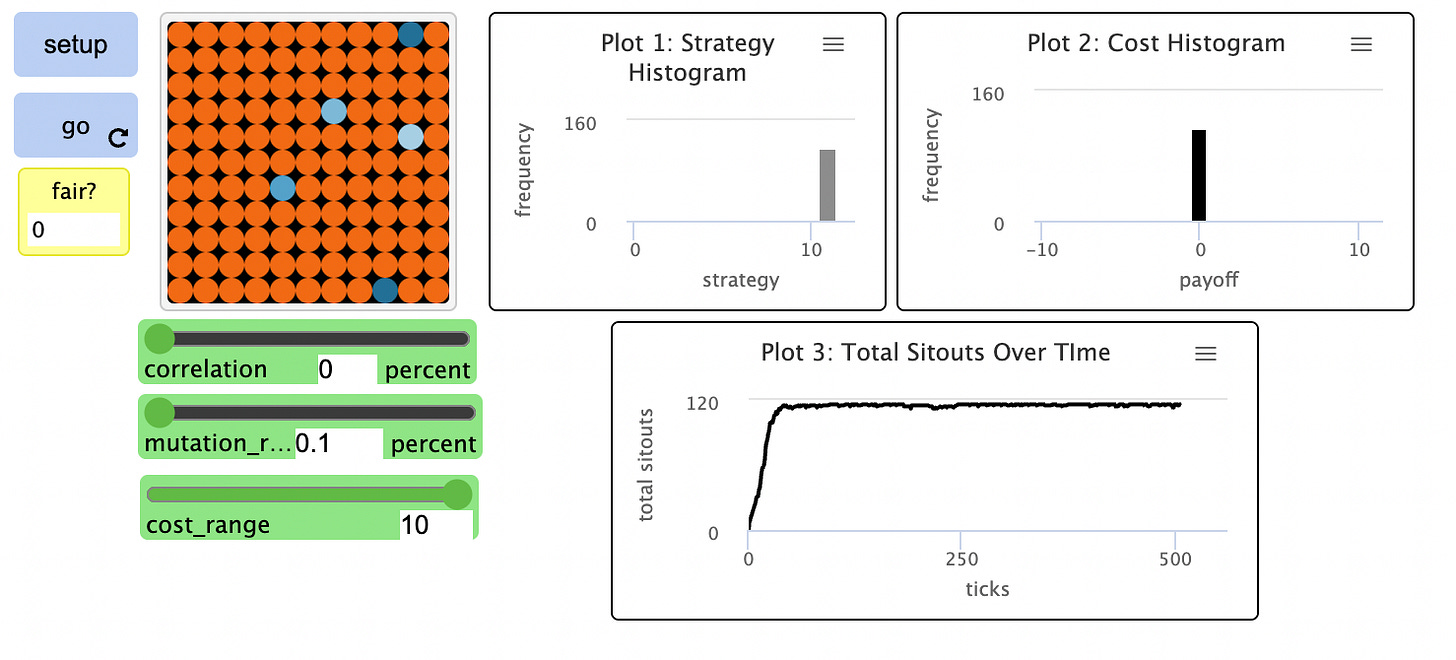

This morsel is essentially a project I completed for COGS303, where we needed to use NetLogo (multi-agent programmable modelling environment) to modify an existing model of the Nash Bargaining game, along with writing up our motivation, implementation, use, analysis, and interpretation of our new model.

Here’s some background, which I’ll try to keep concise at the cost of omitting some details (drop a comment if you’re interested!). The Nash Bargaining game, which was at the heart of this project, involves a pair of ‘agents’ — a fancy word here for a thing that does things since the model doesn’t use ‘people’. These agents simultaneously pick a number between 1-10. If they add up to >10 both agents get 0 and if the sum is lesser or equal to 10 each agent receives their chosen number as a reward. Take a second to run this in your head and it will settle more intuitively. For example, if I pick 6 and my partner picks 4, I receive $6 and my partner receives $4. If they were to pick 5 anticipating I would be super fair like them and also pick 5 but I still picked 6 we’d both get $0. In most cultures and populations, 5 is conventionally considered the fairest choice. Understanding the game itself is the first main step in working through this story.

During class, we modelled this game in NetLogo along with a learning mechanism which randomly assigned an agent as a ‘teacher’ to another agent, who would then mirror their strategy with a probability proportionate to the teacher’s reward, and so more successful strategies get copied more frequently. This learning mechanism has no memory and repeats each round. The learning mechanism is the second key point in this story and begins to explain the transition from the game to the model.

The goal of the building and analyzing model is to look at how often a ‘fairness convention’ (both pick 5) happens compared to unfair conventions. Here’s what those results end up looking like:

We also later incorporated a mutation parameter, which threw in some random number selections to see if one convention would destabilize and flip-flop to the other. Unfair conventions are more unstable, due to the negative outcome of landing with an incompatible partner (e.g. landing with a 6 if you’re a 6). Mutations therefore tend to help push them into the more stable ‘fairness’ convention, at which point they won’t switch back.

To zoom out for a moment, we use models like these not intending to perfectly replicate all intricate human behaviours and their related parameters but to help us test if our most basic sets of assumptions can be compatible with what we observe in real life. It can be a sort of sandbox from which we can make educated predictions from theoretical models. The process itself can also help identify those underlying assumptions to begin with. Models like the Nash Bargaining model can help us understand where fairness norms come from. Since cross-culturally social conventions regarding fairness widely tend to be 50/50 splits, a fairness convention frequency of ~70% in our model might be telling us that we’re missing a factor which might increase that number.

Our job was to motivate a modification which made the model closer to real life by questioning one of its assumptions. For example: do player pairings typically happen randomly? how do people ‘choose’ their teachers? do people copy the most successful strategy or the most common? do individuals play the game the same way with everyone? And so on.

For my model, I thought about how in real life there are systemic, socio-political, economic, and cultural factors which may offer one individual more opportunities and privileges than another — the game rarely starts with an even playing field. Also, the original model only has positive or neutral outcomes ($0-10), but in real life, there is a potential for debts and losses. Not only are direct losses often possible, but there may also be indirect risks or costs associated with playing the game, i.e. an opportunity cost. And so, I thought about how in real life people must learn to weigh the potential costs and benefits of participating in these sorts of social activities, and how this balance varies for every individual and their circumstances which range drastically in time, means, and privilege.

To represent systemic disadvantages across a lifetime I incorporated an associated cost for the game that varies and is randomly assigned to each agent for the duration of a whole experimental run (multiple rounds). The variation in these 'invisible' costs across individuals in the population represents intersectionality and the range of privilege versus disadvantage. As part of the project requirements, we needed to parameterize our new variable, so I included a slider to control the range of costs possible (from 0-10). Additionally, to represent how in real life there is usually the option to abstain from participating in such dealings, I also added an option to sit-out of the game so that no payoffs or costs are applied. Of course, I expected this to be especially attractive when the risk for an individual may be too high. And so, I expected that individuals with higher costs would learn to sit out in order to avoid negative payoffs.

As I forewarned, a decent amount of context to wade through here, but this is where it starts to get juicy. I remember the day I started working on the analysis and rambled to my roommate at 2 am trying to make sense of my model results… good times… I hope your mind gets transported to that 2 am ramble for these next few paragraphs.

Here’s what ended up happening. My model had two stable states: (1) very high total sit-outs (nearly the whole population sits out), which was most likely to happen and be maintained for longer periods when the cost range was lower (2) very low total sit-outs (nearly none of the population sits out), which was more likely to happen and be maintained for longer periods as the cost range increases. Random changes could cause a switch from one stable state to the other.

So why would there be low sit-outs when the range of potential assigned costs was smaller (i.e. the maximum cost is lower)? It makes sense — the majority of agents still had the potential to win something, even if they faced costs that lowered their profit.

Meanwhile, as shown in the example above, when the cost range increased high sit-out conventions were more probable and lasted longer. This is intuitively explained by about half the agents having costs that resulted in null or negative payoffs under the fairness convention.

However, even when costs could range up to 10, the high sit-out convention was not permanent or certain. This is where things got confusing- why would individuals with a high cost still flip-flop? Why would individuals with a low cost still sit out at all?

The first part of the explanation for this phenomenon regards the existence of two stable states based on population averages. Since cost was randomized, at a cost range of 10 the average cost for the entire population was around 5. When a fairness convention occurred, which as mentioned was 70% of the time, the average population payoff was about 5 without costs. So, after applying the cost, both sitting out and playing had, on average, the same expected utility since the overall payoff was 0 in both cases. This balance could be tipped due to chance or random mutations shifting these population averages. Cost ranges decreasing from 10 resulted in the population's average expected payoffs increasing to above 0, making it more favourable than sitting out.

So far, this made sense to me. However, this explanation regards population averages — many individuals were exceptions to this. What was most intriguing was that at cost range 10, even if a high sit-out convention was established for a substantial period of time, there was still a 16% chance the population would drop into the low sit-out convention. In such a circumstance, there were a substantial number of agents that continuously had a negative payoff, as shown in the example below. If they had previously learned to consistently sit out to minimize their cost, what would motivate them to revert to a strategy that puts them at a deficit?

This is where it really starts to get juicy.

The reason was that the learning mechanism was insensitive to individual costs! Agents with high costs could learn from other agents with lower costs who therefore had higher payoffs. High-cost agents would then copy low-cost agents' strategies with no consideration that these strategies did not benefit them in the same way as a result of their unacknowledged disadvantages. When translated back to the real-life context that motivated this model, individuals who had structural barriers might not have benefitted or would be deprived when attempting to copy strategies that brought success to those more privileged than them. In real life, this would be most relevant when a disadvantaged individual is made ignorant of the systemic factors that render these sorts of strategies ineffective and even harmful to them. I see a connection to ideas like that of "the American dream" where the illusion that every citizen has an equal opportunity to 'make it' is pushed to praise those who are privileged or lucky enough to succeed while shaming those who fail. With this ignorance, failure is not attributed to the institutional and social oppression, but rather the perceived inadequacies of that group or individual. In comparison to the findings from our original Nash model, although fairness conventions can hold, the outcomes for individuals were rarely as fair due to varying starting points and opportunity costs.

Now, there are all sorts of further criticisms of the model, for example, the complete ignorance of this learning mechanism is unrealistic. In real life, each individual has a different perception of their status, and may under or overestimate it. This would influence what sorts of risks they feel they have the ability to take. For example, those who have more disadvantages than they believe may attribute failures to themselves and others like them, as we can see with conventions like the model minority myth. Also, the model did not consider that those who may be aware of their costs might be more likely to learn from others with similar costs. In real life, the extent of one's privilege also largely correlates to other social and cultural factors that might make groups of similar status even more inclined to be influenced by one another. And so on.

Now that I’ve taken you down this rabbit hole, let’s find our way back to ‘Plot A’. I highlighted this project because I always thought it was so interesting how relatively simple models could highlight such complex sociopolitical processes if you’re willing to connect enough dots. I went in wanting a simple way to express opportunity costs and risk assessment and was met with initially baffling behaviour that made total sense once I better unpacked the hidden assumptions embedded in my code and likened the resulting process to more nuanced sociopolitical ideas. I also ended up TA’ing for this class, and it was so interesting to see what other students came up with!

Looking back, I might be stretching it but I feel this whole journey lightly resembles an emergent process. The simple rules I set for the system led to intricate results — ones that were more than the sum of the system’s parts. I talk more about my first encounters with the articulated concept of emergence in a moment, but I can’t help but point out this sneaky link.

Lesson & Learning #2: I am a river!

[From PHIL451, Conceptions of the self]

I wrote a whole essay on my personal takeaways from this class, and even that only scratched the surface. So, for the sake of this post, I specifically wanted to highlight some of my favourite metaphors from the texts we covered, since the mental visuals always stuck with me the most. I’ve also noted in square brackets which teaching that metaphor came from (since we covered several). I’ll start with one that has inspired one of my favourite mottos, ‘I am the river!’:

We are all streams in the flow of the river [from Mahāyāna Buddhism]

This idea was drawn from a specific approach to Buddhism called Mahāyāna Buddhism. This teaching puts less emphasis on personal liberation from suffering and more on collective liberation and loving-kindness. This eventually became part of a core value of mine, after building upon the idea with self-reflections, lived experiences, reading up on radical love (particularly Bell Hooks), and reading Hanne De Jaegher’s paper on ‘Loving and Knowing’. Unfortunately, I don’t have a great visual metaphor for that idea yet, so here I’m going to focus on another core idea of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

‘No-self’, emptiness, or anātman refers to how there is no self or enduring identity at any point or place across the series of lives in a cycle. Instead, the end of one life and its associated mental states are causally connected to the next birth in the cycle, aka karma. Much like a river and its changing states of water, there is a persevering existence of the self and yet it holds no single set of constant substance. And so, the sense of an essential ‘self’ is illusory and instead, we are all just products and actors in chains of cause and effect and series of mind and body states.

Although that’s where I got the metaphor from, the phrase itself has taken on an inspired yet personalized meaning. I have always had some trouble pinning down who I am and what makes me me. Was it the things that I liked? My interests? The way I talked or interacted with people? My thoughts? When I was little I used to think of myself kind of like a Rubix cube, being made up of tiles that could be organized and reorganized into hundreds of combinations for each given face. In my adulthood, I found this idea of there being no essential substance in the self to be a useful way to approach coming to terms with an ever-changing self. Although there’s little to grasp onto that won’t slip through your fingers, all is not lost. Chains of causality tether you to all previous, present, and future versions of yourself. In those ripples, if you can watch and listen closely enough, you will never permanently lose any core piece of yourself despite constant evolution. Even in the physical, when all of your original cells get replaced, your new cells will be informed by every cell before them — not only cells of your own but also the cells of all of your ancestors. Like water flowing through and carving meanders into the river, informing the water’s course over millennia, the water that’s flown through me in the past is not forgotten. All of it is part of me, and will always be.

There is relative control but no controller. [from Mahāyāna Buddhism]

Control is a matter of bringing about the right causes and conditions to bear on mental and physical events so as to give rise to the appropriate outcomes or results. This idea comes as a sort of conclusion or by-product of the teaching of ‘no-self’ I just discussed. This built upon what I learned from my very first note on external versus internal loci of control as another insightful way of looking at control.

The farmer who pulls on sprouts to make them grow faster only kills them, but you also can’t neglect them [Mengzi’s Confusianism]

Mengzi compares ethical cultivation to the proper tending of sprouts, and teaches that righteousness is internal: "One must work at it, but do not aim at it directly. Let the heart not forget, but do not help it grow. " Instead, one must direct and plant energy in the right places, and naturally virtue will follow. Slow, steady, and caring habits of tending should be developed. This kind of incremental approach is yet another foreshadowing of the emergence discussion to come.

Butcher Ding, who carves the meat in a flow state with artful skill and ease. He follows the natural curves of the bones and meat and sinue to cut so that his blade glides through effortlessly. [Zhuangzi’s Daosim]

This and the next metaphor come from Zhuangzi’s self-titled Daoist book, which holds an endless supply of beautifully symbolic, humorous, and endearing parables and fables. This story aims to demonstrate what it looks like to flow with the ‘Way’ (Dao) instead of against it. This Dao is reflected in the workings and patterns of nature, and as part of it, we can learn to harness its power to find fulfillment and joy. In the context of ancient China, being a butcher was one of the lowliest professions, but Butcher Ding achieves happiness by perfecting his craft to where he’s able to enter these flow states. From living in the moment and finding contentment in simple things, to being like Butcher Ding, this idea of finding ways to skillfully yet freely and easily meld with the flow is something I come back to a lot.

The boat depends on the water. [From Zhuangzi’s Daoism]

To me, this mental image reminds me that dependence is not contradictory to freedom, as many ‘free’ things in nature depend on other things. Instead, dependence is conducive to it if you know how to flow with it. The boat depends on the water beneath it and the bird depends on the wind beneath its wings to fly. As part of his teachings on the Dao, harmony, and free and easy wandering, Zuangzi also teaches that one must acknowledge and take advantage of dependence to be free in your wandering. I think of this every time I tell a burnt-out friend who does community work and organizing that they are part of the community they wish to uplift and that taking care of themselves is part of their practice, not counter to it.

Last, an honourable mention for a teaching that is not technically a metaphor, but I find this particular way of describing things to be impactful and memorable:

Samsara and nirvana are one, and so nirvana is a state of being rather than a place to be. [from Mahāyāna Buddhism]

For context, samsara describes suffering from the perpetual cycles of birth, life, and death while awakening leads to nirvana: the liberation from this cycle and all further suffering. Using the belief that there is no self, this argues for the compassionate alleviation of suffering itself for all, and hence we get the idea of loving-kindness as an act in service of this goal. The idea of being ‘good’ for the sake of fighting for individual salvation never sat right with me, nor did the idea of living life purely in service of the afterlife. Not only was this suggestion poetic, but I felt it lined up well with the kinds of values I wanted to be able to pull from metaphysical beliefs. This chain of thought later led me down a rabbit hole into Gnosticism and related ancient versions of Abrahamic religions during my journey to further understanding my Coptic identity, which will have to be yet another story for yet another time!

Lesson & Learning #3: the brain is dynamic AND I am a river! (my first introduction to self-organization and emergence)

[From COGS300, Understanding and designing cognitive systems]

In this impassioned annotation of excerpts from Scott Kelso’s Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior, for one of the first times in my undergrad I came across a well-articulated, earnest reading which finally broke me from the shackles of the many static and compartmentalized approaches to the brain I encountered. At this point, no readings had quite put their finger on some of the thoughts and issues I was having in the way this did. You can tell from my notes I was pretty excited :)

This all happened to coincide with my exposure to Adrienne Marie Brown’s Emergent Strategy (which exists more so in the sphere of activism and wellbeing) which altogether reshaped my worldview. At the time, I was also thinking about personal well-being and cultivating mental habits, much inspired by the previous section. Enactive approaches later informed all of this further, especially when it came to identity and conceptions of the self. However, I could spend multiple posts recapping and weaving together all of this along with my non-academic life experiences. In fact, this was all a huge inspiration for my upcoming radio show! So stay tuned! ;)

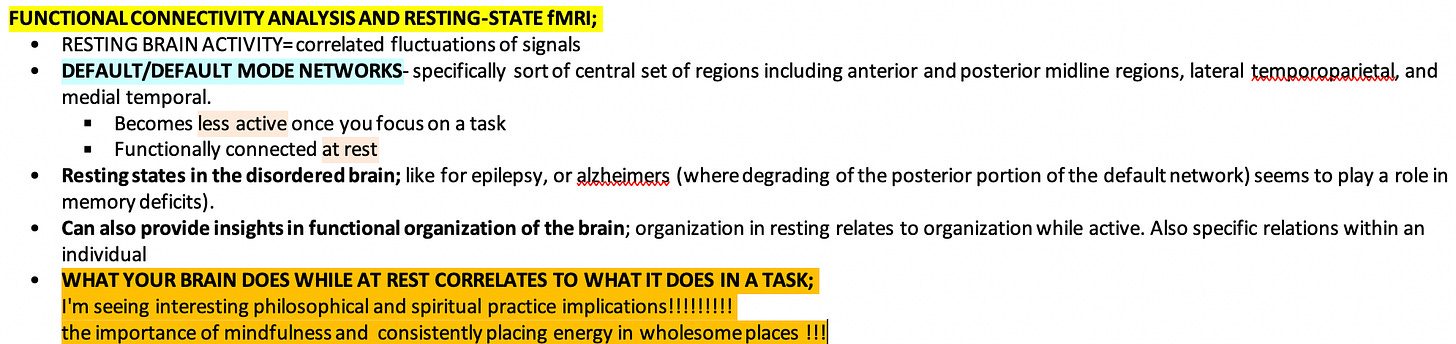

Lesson & Learning #4: the resting state of the mind

[From PSYC365 Cognitive neuroscience]

As Beck would attest, I had plenty of impassioned commentary on the class content of PSYC365. Apart from my notorious knack for pointing out exactly how something was somehow related to colonialism, white supremacy, and capitalism (especially when it came to deficit-centred ways of viewing neurodivergence), this was one of the notes I set aside that I felt had some interesting potential implications. I think this section of my notes succinctly represents the process of understanding the topic in its original context, to my mind leaping ahead and getting excited thinking about the potential implications:

One example of a predictive use of resting-state fMRI was the Anderson paper we looked at, which fascinatingly managed to use ADHD assessment scores in one population to predict ADHD task scores in a completely different population (in a different country!).

Now of course I knowww there are limitations on what we can deduce from this and I am aware of my double-edged tendency to springboard from one idea to another. When I learned about this I was coming off the heels of that philosophy class so I was thinking a lot about developing personal moral frameworks and their associated daily practices. So of course, I found the idea that resting state data could be used predictively fascinating, and although I’m not sure of the direct link, it still ended up underscoring for me the importance of developing mindful habits in my personal practices.

Lesson & Learning #5: the horizonal conception of consciousness and levelling a long-term grudge with the western scientific method

[From PHIL451 Philosophy of the mind]

There were many intricately interesting parts of phil451, but there’s one concept which has stuck with me so well that I wouldn’t have to review all of my notes to explain it and that’s the primacy of consciousness. This perspective proposes that consciousness is a horizon, and so there is no way to get outside of it and describe it in terms of something else.

This was another one of those ideas that clicked right away for me — of course, if everything is necessarily viewed through the lens of our consciousness we cannot get around or see beyond it! But it was wonderful to hear it argued so thoroughly and philosophically argued.

This was a puzzle piece that immediately brought me full circle to a complaint I’ve had since high school: the over-pedestalization of ‘logic’ and ‘rationality’ in Western scientific objectivism. Of course, for me, a lot of the distaste comes from the knowledge that these guiding philosophies are also inextricably historically linked to the false duality of ‘man and nature’ and the pursuit of building man’s control and power over nature. And let’s not even begin to dip our toes into the convenient dehumanization of various groups used to throw them from the box of ‘civilized man’ into ‘the wilderness’ of nature! The pedestalization of 'logic,' 'objectivity,' and 'rationality' — linked to ideals embedded in the foundations of Western science and ways of knowing — are regularly still weaponized in today’s research, often in tandem with (in my opinion) poorly done science which fails to adequately give back to the populations it studies.

It also took me back to another one of Zhuangzi’s assertions I learned in phil451, “Little understanding cannot come up to great understanding; the short-lived cannot come up to the long-lived." As in, the small (humankind) has no experiential basis for being able to understand things beyond their frame of experience (the universe). Our frame of experience is a tiny slice of a vast cosmos with all kinds of creatures, so it is ignorant and foolish for us to think we can confidently extrapolate larger understandings of things beyond our scope.

I felt so strongly about the whole thing I wrote a paper on it for that class, which helped solidify my thoughts on the matter. In that paper, though I did acknowledge that the Western scientific method has certainly proven its strengths, I also argued that if we were to more widely and soberly accept the unsurpassable horizon of consciousness as well as the naivety of true objectivism, our scientific approaches would be better equipped to overcome their current limitations. Moving forward, I wanted to actually ground my science in direct subjective experience, instead of trying to falsely divorce from it. I wanted to move away from pursuing a ‘God's-eye view’ of nature to a view in which we perceive ourselves as both a manifestation of nature and a contributor to its self-understanding, thus rejoining our conceptions of consciousness and nature. I also saw this as an important step towards decolonizing what we think of as ‘science’ — who typically has the power to define what ‘rigorous’ and ‘worthwhile’ science involves? What kind of experiences, ways of knowing, and histories does this inevitably exclude? How can we work towards characters of evidence and theory which honour our commitment to both truth and justice?

All of these realizations came at the perfect time, coinciding with my exposure to qualitative research being done at Beck’s lab. I began to see ways we could begin to achieve this grounding through the earnest incorporation of lived accounts, phenomenal accounts, community-based work, and interdisciplinarity. With my own COGS project also on the horizon, this was a valuable tool in my kit for helping to justify the importance of using things like qualitative research and lived histories and experiences to ground and inform quantitative research questions. Hence, this has been an idea I’ve circled back to many times as I’ve continued working on both my own and others’ qualitative projects at the lab.

Moreover, it’s an idea which has helped shape the kind of career I’d like to lead. For a long time, I’ve been most interested in the health sector and it was just a question of how and what. So many things have shaped my journey in answering that question, from Emergent Strategy (which I alluded to earlier), to decolonialism, to neuroaffirmative and embodied approaches which recognize the body, mind, and surroundings as parts in a dynamic system, as well as the recentering of health maintenance (as opposed to sole focus of ‘pathology’ diagnosis and correction). This ‘lesson & learning’ helped further direct me towards community-based methods which are attentive and affirmative to patients’ subjective experiences, as well as approaches which incorporate a team of individuals with interdisciplinary backgrounds and differing perspectives. I’d like for such values to be embedded and embodied in everything I pursue.

Lesson & Learning #6: hiccups are a reflex of the diaphragm

[From CAPS391 Intro to gross anatomy]

I’ll finish off with the titular learning, from a class where I learned a ton of fascinating anatomy facts. This was the most memorable, partly because I’ve always insisted that the best way to get rid of hiccups is to hold your breath in a particular way: deep breath in, hold, and verrrrryyy slowly breathe out through pursed lips. I’ve also always been a heavy skeptic of the chugging water method. To have the prof confirm that holding and slowing your breath to press and relax the diaphragm is a super legit method was incredibly satisfying (and interesting!). Even more satisfying, chugging or eating fast and getting too full can often be the cause of hiccups in the first place as it can irritate the stomach or esophagus, therefore triggering the reflex! And so, I think back to this every time I get those darn hiccups :)